Ancient Mesopotamia's Social Hierarchy: Unveiling Its Complex Fabric

Table of Contents

- The Cradle of Civilization and Its Urban Complexity

- The Foundational Pyramid: Understanding Mesopotamia's Social Structure

- Royalty and the Ruling Elite: At the Apex of Power

- The Upper Class and Gentry: Pillars of Society

- The Middle Class: The Backbone of Mesopotamian Life

- The Lower Class: Laborers and the Enslaved

- Social Mobility and Evolution of the System

- Daily Life and Inter-Class Dynamics

The Cradle of Civilization and Its Urban Complexity

The very concept of a "cradle of civilization" implies the emergence of foundational elements that underpin complex human societies, and in Mesopotamia, the rise of cities was paramount. These urban centers were not just collections of dwellings; they were vibrant hubs of activity, commerce, and governance, demanding a sophisticated social framework to manage their burgeoning populations. The population of ancient Mesopotamian cities varied greatly, reflecting their varying scales of influence and development. For instance, around 2300 BCE, Uruk, a prominent city, boasted a population of 50,000. In contrast, Mari, situated to the north, had a population of 10,000, while Akkad supported 36,000 inhabitants (Modelski, 6). The sheer size and density of these urban populations inherently led to a more intricate and stratified social life. As more people gathered in a single area, the need for organized governance, resource distribution, and specialized labor became critical. This necessity gave rise to a division of labor and, subsequently, a division of social classes. Just like societies in every civilization throughout history, the populations of these cities were divided into social classes, each with specific roles and responsibilities. This fundamental shift from smaller, more egalitarian communities to large, complex urban centers was a driving force behind the development of the sophisticated Mesopotamian social hierarchy.The Foundational Pyramid: Understanding Mesopotamia's Social Structure

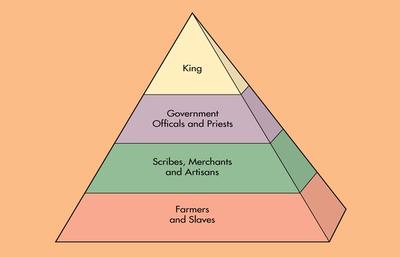

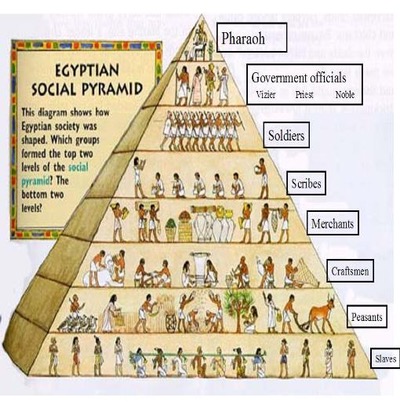

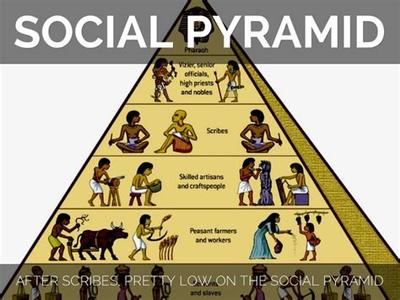

The hierarchy of Mesopotamia can be aptly symbolized as a triangle-shaped pyramid, a visual representation that clearly illustrates the distribution of power, wealth, and status. At the very top, the narrow peak represented the supreme authority, while the broad base supported the vast majority of the population. This highly stratified structure was a defining characteristic of ancient Mesopotamian society. In a broader sense, the top of this pyramid consisted of the king and his immediate circle, holding ultimate authority. The Mesopotamian social hierarchy basically consisted of three primary classes: nobility, free citizens, and slaves. However, a more detailed breakdown often divides Mesopotamia's social hierarchy into four distinct categories: royalty, upper class, middle class, and lower class. Each group was made up of various members of society, performing specific functions that contributed to the overall functioning of the civilization. The history of the social system in Mesopotamia is somewhat obscured by the lack of familial documentation, such as lists of family ties or family surnames, with Mesopotamians typically referred to by their first name. Despite this historical ambiguity, the general structure of the social pyramid is well-understood, outlining the roles and statuses from the highest echelons of power to the lowest ranks of labor.Royalty and the Ruling Elite: At the Apex of Power

At the very pinnacle of the Mesopotamian social hierarchy stood the royalty and nobility, embodying the supreme authority and divine mandate that governed the land. This exclusive group held immense power, wealth, and influence, shaping the destiny of their cities and empires.The King: Divine Authority and Earthly Duties

The king was undeniably the top rank holder of the Mesopotamia social hierarchy. His position was not merely political; it was often imbued with religious significance, as kings were frequently seen as chosen by the gods or even as divine representatives on Earth. The monarch's primary duties were extensive and multifaceted, encompassing both spiritual and temporal responsibilities. The king was responsible for creating and enforcing laws, ensuring justice, leading the military in times of war, and overseeing the vast administrative machinery of the state. He was the ultimate decision-maker, the chief priest, and the supreme commander, embodying the very essence of the Mesopotamian state. His decrees were law, and his word was absolute, reflecting the centralized nature of power in these early civilizations. The king's household, including the royal family, was also part of this elite stratum, enjoying unparalleled privileges and living a life far removed from the common populace.Priests and High Officials: Guardians of Faith and Administration

Closely aligned with the king, and often part of the broader "upper class" or "gentry," were the high priests and other government officials. In a society where religion permeated every aspect of life, priests wielded immense power and influence. They were the intermediaries between humans and the gods, responsible for rituals, sacrifices, and interpreting divine will. Temples, which were often the largest and most impressive structures in Mesopotamian cities, served as economic powerhouses, owning vast tracts of land and employing numerous people. The chief priests, therefore, held significant economic and political sway, often advising the king and participating in governance. Alongside the priestly class were other high-ranking government officials and wealthy merchants. These individuals managed the day-to-day affairs of the kingdom, from tax collection and public works to diplomatic relations and trade. Their positions were often hereditary or granted based on merit and loyalty to the crown. Their wealth, derived from land ownership, trade, or their official capacities, solidified their status within the upper echelons of the Mesopotamian social hierarchy. Together, the king, royal family, priests, and wealthy merchants formed the ruling class, dictating the direction and stability of ancient Mesopotamian society.The Upper Class and Gentry: Pillars of Society

Beneath the king and the royal family, but still firmly within the elite segment of the Mesopotamian social hierarchy, was the upper class, often referred to as the gentry. This group constituted the non-royal but highly influential members of society whose status was primarily based on their wealth, land ownership, and significant roles within the administrative or economic spheres. This class included government officials, who managed the bureaucracy of the state, ensuring that royal decrees were implemented and taxes collected. Landowners, who controlled vast agricultural estates, formed another crucial segment of this class, deriving their wealth and influence from the produce of their lands and the labor of those who worked them. Wealthy merchants also belonged to this upper stratum. Mesopotamia was a hub of trade, connecting distant regions through intricate networks. Merchants who successfully navigated these routes, importing valuable resources and exporting local goods, accumulated considerable fortunes. Their economic power often translated into social and political influence, allowing them to participate in important civic decisions or even lend money to the state. These individuals lived lives of relative comfort and luxury, possessing fine homes, elaborate clothing, and access to education and cultural pursuits. Their contributions were vital for the economic prosperity and administrative stability of the Mesopotamian state, acting as key intermediaries between the ruling elite and the broader populace.The Middle Class: The Backbone of Mesopotamian Life

The middle class formed the substantial backbone of the Mesopotamian social hierarchy, comprising the "free citizens" who, while not possessing the immense wealth or power of the upper echelons, were nonetheless vital to the daily functioning and economic vitality of society. This diverse group included skilled artisans, scribes, soldiers, and a significant portion of the farming population who owned their own land. Artisans, such as potters, weavers, metalworkers, and carpenters, played a crucial role in producing the goods necessary for daily life, trade, and monumental construction. Their specialized skills were highly valued, and they often worked in workshops, contributing significantly to the urban economy. Scribes, the keepers of knowledge and the administrators of bureaucracy, were particularly esteemed. Given that writing (cuneiform) was a complex skill, scribes underwent extensive training and were indispensable for recording laws, managing trade, documenting history, and administering temple and state affairs. Their literacy granted them a unique position of influence and respect within the Mesopotamian social structure. Soldiers, essential for defense and expansion, also belonged to this class. They protected the cities and empires, ensuring security and enforcing the king's authority. Farmers, particularly those who owned their land, formed a significant portion of the middle class, providing the agricultural surplus that fed the burgeoning urban populations. Their labor was fundamental to the very survival of the civilization. Interestingly, the old Sumerian social order, known for its strong middle class, was mostly restored after the fall of the Akkadian Empire, indicating the enduring importance and resilience of this societal segment. However, society in Mesopotamia became mostly feudal about the middle of the 2nd millennium BCE, suggesting shifts in land ownership and social relations over time. Despite these changes, the middle class remained the engine of Mesopotamian society, driving its economy and sustaining its daily life.The Lower Class: Laborers and the Enslaved

At the base of the Mesopotamian social hierarchy lay the largest segment of the population: the lower class, which included common free citizens who were laborers and, at the very bottom, slaves. This broad category represented the workforce that physically built and sustained the Mesopotamian civilization.The Common Free Citizens and Laborers

This group consisted of free individuals who did not own significant land or possess specialized skills that would elevate them to the middle class. They often worked as agricultural laborers on temple or royal lands, as unskilled construction workers on monumental projects like ziggurats and city walls, or as servants in wealthier households. Their lives were characterized by hard labor, limited resources, and a constant struggle for subsistence. While they were free and had certain rights under the law, their daily existence was often precarious, dependent on harvests, the will of their employers, and the stability of the state. They were the backbone of the economy, providing the physical labor necessary for all aspects of Mesopotamian life, from food production to urban development.Slaves: The Foundation of Labor

At the very bottom of the Mesopotamian social hierarchy were the slaves. Slavery in Mesopotamia was not always based on race or ethnicity; individuals could become slaves due to debt, as prisoners of war, or by being born to enslaved parents. Debt slavery was particularly common, where individuals or families would sell themselves or their children into servitude to pay off debts. Slaves performed a wide range of tasks, from arduous manual labor in fields, mines, and construction sites to domestic service in wealthy households. Some skilled slaves might even work as artisans or scribes, though their output belonged to their masters. While their lives were often harsh and their freedoms severely restricted, Mesopotamian law did provide some protections for slaves, and in certain circumstances, they could even buy their freedom. Despite these occasional avenues for manumission, slaves represented the most vulnerable and exploited segment of the population, their labor forming a fundamental, albeit often invisible, foundation for the prosperity and achievements of ancient Mesopotamian society.Social Mobility and Evolution of the System

While the Mesopotamian social hierarchy was highly stratified and rigid, it was not entirely static. There were instances, albeit limited, of social mobility, and the overall structure itself evolved over millennia. Individuals could potentially move up the social ladder through exceptional skill (e.g., a talented artisan or scribe), military prowess, or by accumulating wealth through trade. For instance, a common soldier might rise through the ranks to become a respected officer, or a clever merchant might amass enough fortune to join the ranks of the wealthy gentry. Debt slaves, as mentioned, could sometimes work off their debts or be manumitted by their masters. The historical evolution of the Mesopotamian social system also saw significant shifts. The provided data highlights that the old Sumerian social order, characterized by a strong middle class, was largely restored after the collapse of the Akkadian Empire. This suggests a cyclical nature of societal organization, where certain values or structures might re-emerge after periods of upheaval. However, a more profound transformation occurred around the middle of the 2nd millennium BCE, when society in Mesopotamia became mostly feudal. This transition likely involved a shift in land ownership patterns, with more land being controlled by powerful lords or kings, and common farmers becoming tenants or serfs tied to the land, rather than independent landowners. Such changes would have fundamentally altered the dynamics between classes, potentially solidifying the power of the elite and further entrenching the lower classes in their positions. These evolutions demonstrate that even in ancient times, social structures were not immutable but rather dynamic systems responding to political, economic, and military developments.Daily Life and Inter-Class Dynamics

The intricate Mesopotamian social structure profoundly influenced the daily lives and interactions of its inhabitants. Each distinct social class had specific roles that contributed to the functioning of society, creating a complex web of interdependence. Understanding these classes helps us grasp the complexities of ancient Mesopotamian society and how its members navigated their world. For the king and the ruling elite, daily life revolved around governance, religious ceremonies, and maintaining order. Their interactions were primarily with high-ranking officials, priests, and military commanders, focused on strategic decisions and the management of the state's resources. The upper class, consisting of wealthy merchants, landowners, and high-ranking officials, engaged in trade, managed their estates, and participated in civic life, often interacting with the ruling elite and overseeing the work of the middle and lower classes. Their lives were characterized by relative comfort and access to luxury goods. The middle class, comprising artisans, scribes, and free farmers, experienced a more varied daily life. Artisans spent their days crafting goods, interacting with customers and suppliers. Scribes were engaged in writing, record-keeping, and administrative duties, often working in temples or palaces, interacting with all levels of society. Free farmers toiled in the fields, their lives dictated by the agricultural calendar, interacting with their communities and occasionally with landowners or tax collectors. Their interactions with the upper classes were often transactional, while their social lives revolved around their families and local communities. At the base, the lower class and slaves faced the most arduous daily lives. Their interactions were primarily with their immediate families, fellow laborers, and their overseers or masters. Their existence was largely defined by physical labor, whether in the fields, construction sites, or as domestic servants. They had the least autonomy and their lives were often dictated by the needs of the classes above them. A unique aspect of Mesopotamian social interaction, as highlighted by the provided data, is the history of the social system being somewhat obscured by the lack of familial documentation such as lists of family ties or family surnames. Mesopotamians were typically referred to by first name, suggesting that while social status was paramount, individual identity within one's immediate community might have been more emphasized than broader familial lineages in certain contexts. This contrasts with later societies where surnames became crucial for tracking family wealth and status. Despite this, the distinct social classes each had specific roles that contributed to the functioning of society, creating a vibrant, albeit rigidly structured, social tapestry.Conclusion

Mesopotamia, truly the "cradle of civilization," boasts a remarkably complex and hierarchical social structure that played a vital role in shaping its ancient society. From the supreme authority of the king at the pyramid's apex to the foundational labor provided by slaves at its base, every layer of the Mesopotamian social hierarchy was integral to the functioning and achievements of this groundbreaking civilization. The distinctions between royalty, the upper class, the middle class of free citizens, and the lower class including slaves, dictated daily life, opportunities, and responsibilities, creating a highly stratified yet remarkably organized society. Understanding the nuances of this ancient Mesopotamian social structure provides invaluable insights into how early complex societies managed large urban populations, distributed labor, and maintained order over millennia. It reveals the intricate interplay between governance, economy, religion, and the everyday lives of people who lived in Mesopotamia thousands of years ago. The legacy of this social organization, with its emphasis on hierarchy and specialized roles, undoubtedly influenced subsequent civilizations. What aspects of ancient Mesopotamian social life do you find most fascinating? Share your thoughts in the comments below! If you're eager to delve deeper into the wonders of ancient civilizations, explore our other articles on the history and culture of these foundational societies.

This pyramid shows the social classes of Mesopotamia. This shows the

Social Hierarchy Of Mesopotamia

Share